An Intuitive Introduction to Gaussian Processes

Deep learning is currently dominated by parametric models, which are models with a fixed number of parameters regardless of the size of the training dataset. Examples include linear regression models and neural networks.

However, it’s good to occasionally take a step back and remember that that is not all there is. Non-parametric models like k-NN, decision trees, or kernel density estimation don’t rely on a fixed set of weights, but instead grow in complexity based on the size of the data.

In this post we’ll talk about Gaussian processes, a conceptually important, but in my opinion under-appreciated non-parametric approach with deep connections with modern-day neural networks. An interesting motivating fact which we will eventually show is that neural networks initialized with Gaussian weights are equivalent to Gaussian processes in the infinite-width limit.

Why is it called a Gaussian process?

The behavior of a (possibly multi-dimensional) random variable can be characterized by its probability distribution, i.e the bell curve for a Gaussian random variable.

What if we now consider the probability distribution over random functions? The generalization from variables to functions is called a stochastic process. If we restrict our attention to only processes which follow a Gaussian distribution, then the computations required for learning and inference becomes relatively easy.

Motivation

In this post, we concern ourselves with using Gaussian processes for supervised learning, which can take on the form of either regression or classification.

Suppose we have a set of input points with their associated values, and we would like to find a function that interpolates through all these values.

However, there are uncountably many such functions, and so how do you decide which is the best one to use?

There are two approaches to this:

- You can restrict the class of functions that you consider (i.e all decision trees with depth at most 3). However, this runs the risk of choosing a hypothesis class that is too restrictive and hence you get a poor model, or otherwise one that is too large and you get overfitting.

- You can place a prior over all possible functions, where you put more probability mass on functions that have nice properties like smoothness. However, a-priori it is unclear how to compute this since there is an uncountable number of functions.

This is where Gaussian processes come in. We can imagine a function to be an (uncountably) infinite dimensional vector, where each coordinate encodes the values that the function takes on. The goal is to restrict the set of functions to only those which are consistent with a training dataset, i.e taking on a particular value. Then the wonderful thing with Gaussian Processes is that by only considering this finite set of dataset point, you get the same model as if you considered the value at every uncountably-many point, making this computationally tractable.

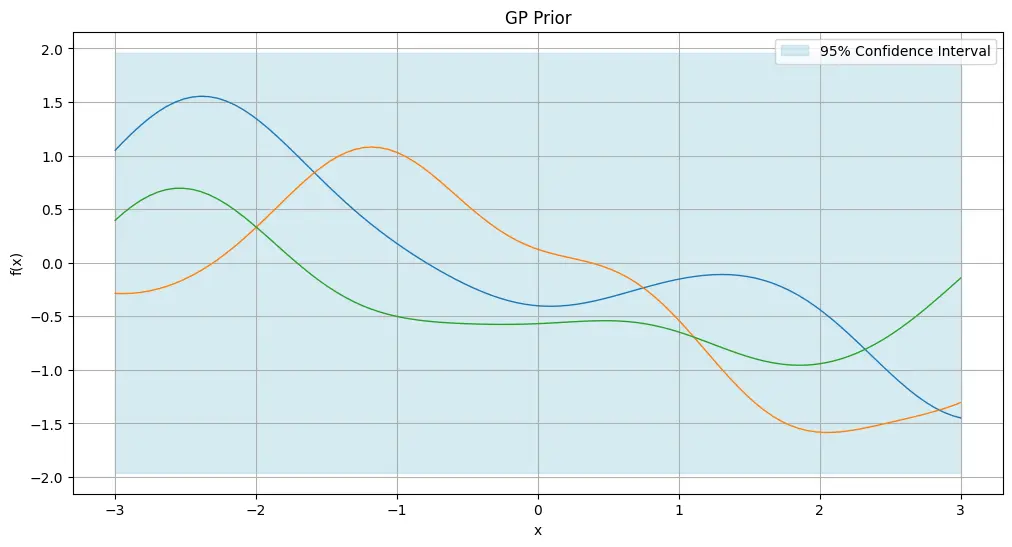

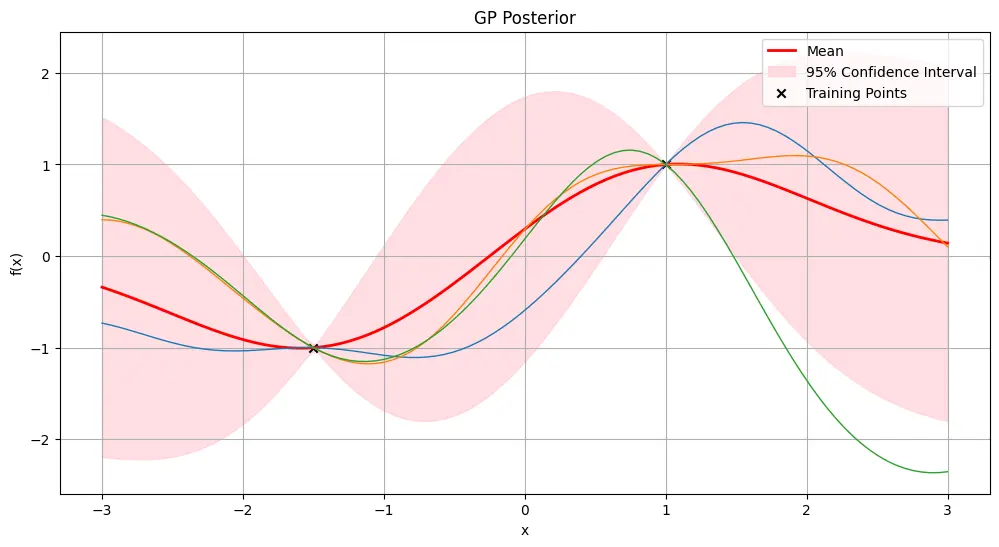

Below is an illustration of what this looks like:

We make some preliminary observations without worrying too much about what is precisely happening yet:

- Observe via the confidence interval that our prior is centered with mean 0, and 1 standard deviation (and hence $\pm$1.96 for a 95% confidence interval).

- Notice how the confidence bands shrinks at the observed points, and increases as we get further from these points. This is due to our specific choice of kernel (explained later) used for the Gaussian process, which makes the assumption that points which are closer together tend to be more correlated in their values.

Let’s see it try to fit a random smooth function as we increase the number of randomly sampled training datapoints:

It is possible that sampling the underlying function is expensive, and we want to minimize the number of samples we make before getting a good fit.

We can be smart about this by prioritizing sampling regions where there is most uncertainty:

You can also use Gaussian processes for time-series prediction, where you can now quantify uncertain in future values. Here’s an example of predicting the price of NVDA’s over the last 120 days from when the post was written:

Well.. it certainly doesn’t really do too great here as Gaussian process kernels usually assume stationarity, which means that the statistical characteristics of the data (i.e mean, variance, autocorrelation) doesn’t change over time, which is definitely not what is happening in the stock market. Still worth a shot though!

Hope these examples help to motivate why Gaussian processes are cool.

Let’s now do a quick review of Bayesian modelling before diving right in.

Bayesian Modeling

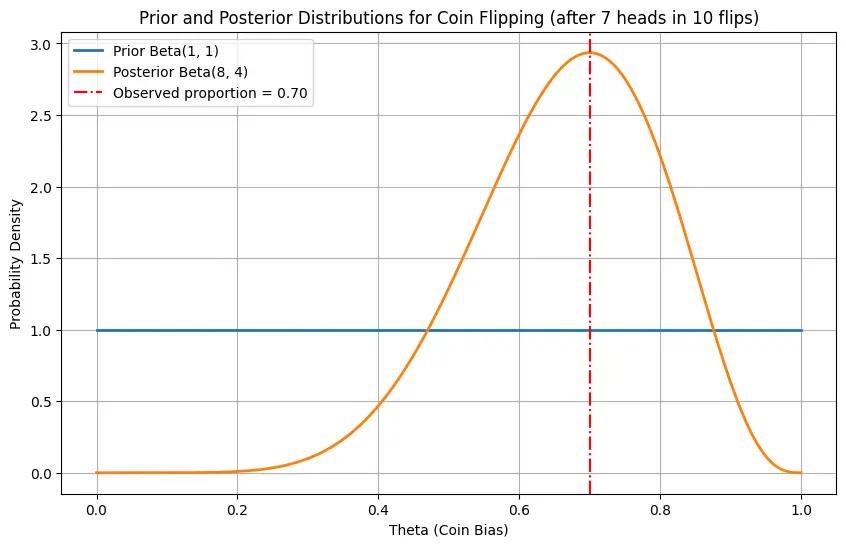

In Bayesian modeling, we start off with a prior that represents our beliefs about our data. For instance, before flipping a coin to determine its bias $\theta$ we can have a uniform prior $p(\theta)$ on the bias it could take. This can be represented by the beta distribution $\textrm{Beta}(\alpha=1, \beta=1)$, which is used as it happens that its posterior update is also a beta distribution with different parameters, which makes the update computationally simple.

We perform many coin flips, and can use the results $\mathcal{D}$ to update our beliefs about $\theta$. Our new beliefs about the distribution of $\theta$ is referred to as the posterior distribution.

The update for the posterior is given by Baye’s rule:

\[\textrm{posterior} = \frac{\textrm{likelihood} \times \text{prior}}{\text{marginal likelihood}},\]which in this case is given by

\[p(\theta \mid \mathcal{D}) = \frac{ p(\mathcal{D} \mid \theta) p (\theta)}{p(\mathcal{D})} = \frac{ p(\mathcal{D} \mid \theta) p (\theta)}{\int p(\mathcal{D} \mid \theta) p(\theta) \, d \theta},\]where the denominator in the second form marginalizes over all possible priors, as we usually do not know $p(\mathcal{D})$ directly.

The posterior distribution for $\theta$ for coin flipping can be shown to also follow the beta distribution, visualized below:

Finally, after we have “trained” our model with our data, we can also get the probability of observing test datapoints $\mathcal{D}_*$ given our posterior. This is known as the predictive distribution, given by:

\[p(\mathcal{D}_* \mid \mathcal{D}) = \int p(\mathcal{D}_* \mid \theta) p(\theta \mid \mathcal{D}) \, d \theta\]For instance, in the coin flipping case, the probability that we observe another heads would be the mean of the beta posterior distribution, i.e 0.7.

Gaussian Processes

Definition

For simplicity, let’s consider the space of real processes $f(x) : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ (it is straightforward to generalize this to multiple dimensions).

A Gaussian process can be completely specified by its mean function $m(x)$ and covariance function $k(x, x’)$ of a real process $f(x)$, given by:

\[\begin{align} m(x) & = \E [f(x)], \\ k(x, x') & = \E_{x, x'} [(f(x) - m(x))(f(x') - m(x'))]. \end{align}\]This can be written as

\[f(x) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x), k(x, x')).\]For notational simplicity we will assume the mean to be zero.

The covariance function hence places a restriction on the functions $f$ that is possible under the data.

The Covariance Function

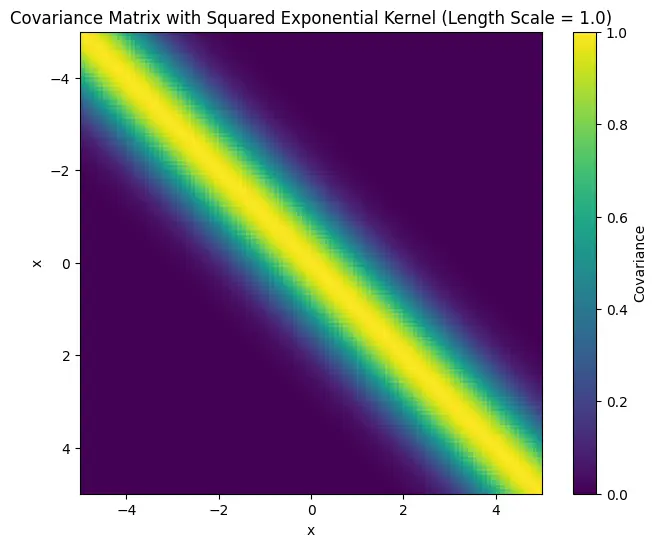

A common choice for the covariance function is the squared exponential (SE) function, also called the Radial Basis Function (RBF):

\[\textrm{cov}(f(x), f(x')) = k(x, x') = \exp \left( -\frac{(x-x')^2}{2 \sigma^2} \right)\]We see the correlation between the values that $x$ and $x’$ takes on $f$ follows a Gaussian distribution of their difference: it is close to 1 when they are close, and decays to 0 as they are farther apart.

Here’s a visualization of the covariance matrix with $\sigma=1$ over equally spaced points:

Predicting with Gaussian Processes

For simplicity, consider the case where we make $n$ observations of data $(x_1, f_1), \cdots, (x_n, f_n)$. Use $\mathbf{X}$ and $\mathbf{f}$ to denote the vector of training inputs and outputs respectively.

We have a set of test inputs $\mathbf{X}_*$, and we are interested to know what are likely values that it could take on given the training data.

This means we can model the joint distribution of the training data with the test inputs as follows, where the set of possible functions must respect the structure of the covariance function:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{f} \\ \mathbf{f}_* \end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N} \left( \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} \\ \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) & \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}_*) \\ \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}_*, \mathbf{X}) & \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}_*, \mathbf{X}_*) \end{bmatrix} \right),\]One may begin to worry that this is impossible to compute, but very fortunately it turns out that the posterior is also Gaussian:

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{f}_* & \mid \mathbf{X}_*, \mathbf{X}, \mathbf{f} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{\mu}_*, \mathbf{\Sigma}_*), \\ \text{where:}\\ \mathbf{\mu}_* &= \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}_*, \mathbf{X}) \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{f}, \\ \mathbf{\Sigma}_* &= \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}_*, \mathbf{X}_*) - \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}_*, \mathbf{X}) \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}_*). \end{align}\]Then to determine what values $\mathbf{X}_*$ could take on, one approach would be to sample from this Gaussian distribution.

\(\newcommand{\fstar}{\mathbf{f}_*} \newcommand{\mustar}{\mathbf{\mu}_*}\) Another approach using the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate would require simply taking the posterior mean, i.e $\fstar = \mustar$.

Code Walkthrough

Let’s see everything in code to make things concrete:

Relation to Neural Networks

In the next blog post, we will show how a neural network initialized with Gaussian weights converges to a Gaussian process in the infinite width limit.

Related Posts: