The Delightful Consequences of the Graph Minor Theorem

The graph minor theorem, also known as the Robertson–Seymour theorem, is generally regarded as the most important result in graph theory. In this post we introduce the graph minor theorem, provide the necessary background, and discover its delightfully deep algorithmic and philosophical implications.

Graph Minors

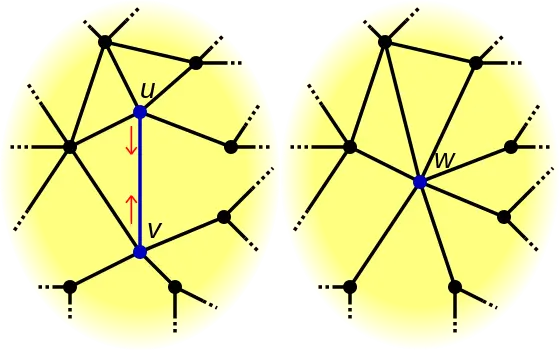

An edge contraction is illustrated by the diagram below, where you take an edge connected by two vertices (u) and (v), and combine them to form a new vertex (w) that still preserves the old adjacencies but eliminates duplicate edges.

Quasi-Orders and Well-Quasi Orders

A quasi-order is a relation that is reflexive and transitive. We build on this to define a well-quasi-order:

A very useful implication of a well-quasi-order that is not hard to show is the following:

We will make use of the fact that it cannot have infinite anti-chains later.

The Graph Minor Theorem

In 1960, Kruskal had already proved that finite trees are well-quasi-ordered by the topological minor relation (instead of allowing edge contractions, a topological minor allows edge subdivision). In contrast, proving the graph minor theorem was a Herculean effort that took over 20 years (1983-2004), involving over 500 pages. It says the following:

At first glance, the statement may not seem very impressive. However, we get a lot of mileage out of it if we consider its implications on minor-closed properties:

Many interesting graph properties are minor-closed, such as planarity (whether a graph is drawable on a plane without any intersecting edges) and the tree-width of a graph (the tree-width of a graph roughly speaking is how much it resembles a tree; trees have tree-width 1).

Now consider any minor-closed property \(\mathcal{P}\) that we are interested in. We can define the (possibly infinite) set \(\mathsf{Forb(\mathcal{P})}\) to contain all graphs without property \(\mathcal{P}\). We can think of these as all the bad graphs where if a graph \(G\) contained any of them as a minor, then we are sad as \(G\) will not have property \(\mathcal{P}\).

Furthermore, we can further reduce the characterization of this bad set by only considering keeping the smallest representative of each chain (i.e pairwise comparable elements). This gives us the unique smallest set known as the Kuratowski set \(\mathcal{K}_\mathcal{P}\), which contains the minimal elements of \(\mathsf{Forb(\mathcal{P})}\) with respect to minors.

But then this means that the elements of \(\mathcal{K}_\mathcal{P}\) must all form an antichain, since they are minimal. The graph minor theorem tells us that the minor relation is a well-quasi order, and early at the start we saw how a well-quasi-order implies that there cannot be infinite antichains. This demonstrates that \(\mathcal{K}_\mathcal{P}\) is in fact finite!

This is delightful news for us, because it means that for any graph property \(\mathcal{P}\) of interest, we only need to keep a finite database of all the graphs in \(\mathcal{K}_\mathcal{P}\), and then in the future whenever someone hands us a graph \(G\) and asks us if it has \(\mathcal{P}\), we can simply check if any of the entries in the database is a minor of \(G\), and if it is not the case, we give them a wide grin and tell them that \(G\) does have the property, and if not, we gently pat them on the back and ask them to come back with another graph tomorrow.

One may still worry that testing if one graph is a minor of another may be prohibitively slow, but in fact Robertson and Seymour also showed in 1995 that this could be done efficiently in cubic time! So now you are all ready to go to build your new SaaS Y Combinator startup that helps companies and governments all over the world test whether a graph NFT that they paid a lot of money for actually satisfies a property \(\mathcal{P}\), but wait a moment, your chief database engineer objects. She asks about where we can find the appropriate \(\mathcal{K}_\mathcal{P}\) to load into the company’s shiny new Hadoop clusters. You scratch your head for five minutes before realizing that this is an open problem (for most \(\mathcal{P}\)), and sadly come to the realization that you just pulled off the investor fraud of the century.

To close off this post, I leave you with a final story about the remarkable implications of the graph minor theorem. Previously, it was unknown whether the problem of determining if a graph in 3D space can be embedded such that it is knotless is decidable (linkless embedding). However, the graph minor theorem not only showed that it was decidable, it gave a polynomial time algorithm for doing so!

References

- Reinhard Diestel. Graph Theory. Springer, 2018.

Related Posts: