Efficient Low Rank Approximation via Affine Embeddings

Affine Embeddings

Suppose we have a \(n \times d\) matrix \(A\) that is tall and thin, and a \(n \times m\) matrix \(B\) that can have a very large number of columns. The goal is to solve

\[\begin{equation} \min_X | AX - B|_F^2. \end{equation}\]An affine embedding is a matrix \(S\) such that

\[\begin{equation} \label{eq:affine_desired} \|S(A X-B)\|_{\mathrm{F}}=(1 \pm \varepsilon)\|A X-B\|_{\mathrm{F}} \end{equation}\]holds with high probability. CountSketch matrices are one class of matrices that can be used for affine embeddings. CountSketch matrices are \(k \times n\) matrices with \(k = O(d^2/\varepsilon^2)\), and where one entry is taken per column at random and set to \(\pm 1\) with equal probability, with all other entries zero.

For the rest of this post, we will see how to apply affine embeddings to help solve low-rank approximations.

Low-Rank Approximation

Low-rank approximation is also referred to as Principal Component Analysis (PCA). It is one of the most popular ways of performing linear dimensionality reduction, with other more complicated ways being via neural networks.

Motivation

Suppose you have a \(n \times d\) matrix \(A\), where both dimensions are large. This could represent something like a customer-product matrix used in online recommender systems, where each cell \(A_{i,j}\) denotes how many times customer \(i\) purchased item \(j\). Then it is typically the case that \(A\) can be well-approximated by a low-rank matrix. For instance, using the previous example, there might only be a few dominant patterns that describes purchasing behavior in \(A\), and the rest of it is just noise.

Therefore, if we can find such a low-rank approximation, we can achieve significant space savings, and can also help to make the data more interpretable.

We can thus formulate our problem as finding a rank-\(k\) matrix \(A_k\) such that

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:best-rank-k} \argmin_{\text {rank-$k$ matrices $B$} }\|A - B\|_{\mathrm{F}} \end{equation}\]Exact Solution: Truncated Singular Value Decomposition

A natural solution that comes to mind is to use truncated singular value decomposition (SVD), which in fact gives us the best rank-\(k\) approximation for \(A\) as per Equation \ref{eq:best-rank-k}. To approximate the \(n \times d\) matrix \(A\) with a rank-\(k\) matrix, compute the SVD of \(A\) to get \(A=U \Sigma V^{\top}\). Define \(\Sigma_{k}\) by zeroing out all the singular values in \(\Sigma\) below the \(k\)-th row, and define \(A_{k}=U \Sigma_{k} V^{\top}\). Note that we can also drop all but the top \(k\) rows or \(V^{\top}\) and drop all but the top \(k\) columns of \(U\) without changing \(A_{k}\).

It turns out that \(A_{k}\) minimizes \(\left\|A_{k}-A\right\|\) among all rank-\(k\) matrices for many norms, including the Frobenius norm and the spectral norm. More generally, \(A_{k}\) is the best rank-\(k\) approximation under any unitarily invariant norm.

We can compute the SVD of \(A\) in \(O\left(\min \left(n d^{2}, n^{2} d\right)\right)\) time. The \(\min\) comes from the fact that we can transpose \(A\) if necessary before performing SVD, so that the linear dimension matches the larger dimension.

However, the problem is that performing SVD is too expensive, since \(n\) and \(d\) are large.

Approximate Solution: Truncated Singular Value Decomposition

In order to get a better runtime, we relax the problem such that we are satisfied with an approximate solution instead of an exact solution. Our goal is now to find a rank \(k\) matrix \(A'\) such that

\[\begin{equation} \left\|A^{\prime}-A\right\|_F \leq(1+\varepsilon)\left\|A_{k}-A\right\|_F \end{equation}\]with a constant failure probability (say 9/10).

We will now show an algorithm that can do this \({O(\nnz{A} +(n+d) \operatorname{poly}(k / \varepsilon))}\) time, due to Woodruff, Clarkson, and Sarlos~\cite{Woodruff-LRA}~\cite{sarlos}. Recall that \(\nnz{A}\) is the number of non-zero entries in \(A\). When the input is dense, this is in approximately \(O(n d)\) time, which is significantly faster than SVD. When it is sparse, it becomes even faster.

Intuition

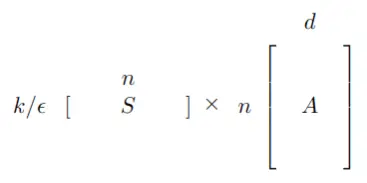

The key idea is to compute \(SA\), such that the number of rows of \(S\) is \(O(k/\epsilon)\) which is small.

Think of the rows of \(A\) as points in \(\mathbb{R}^d\). Think of \(SA\) as taking a small number of linear combinations of \(A\), where each row of \(S\) is picking a random linear combination of all the rows of \(A\), i.e points in \(\mathbb{R}^d\):

This allows us to think of \(SA\) as a \(\frac{k}{\epsilon} \times d\) matrix where we performed this operation \(k/\epsilon\) times. Then each row of \(SA\) is a linear combination of the rows of \(A\), but now in a subspace of only dimension \(k/\epsilon\). If we run SVD on these projected points, we can do it in only \(O \left( n\left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)^2 \right)\) time!

To summarize, the main idea is to:

- Project all the rows of \(A\) onto a lower dimensional space \(SA\).

- Find the best rank-\(k\) approximation to the points in \(SA\) via SVD.

Choice of Sketching Matrix

One might wonder which sketching matrices \(S\) would work for this paradigm. In fact, all of the following sketching matrices work:

- \(S\) as the \(\frac{k}{\epsilon} \times n\) matrix of i.i.d normal random variables. We can compute \(SA\) in time \(O\left( \nnz{A} \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\) since \(S\) is dense. However, we could do a lot better.

- \(S\) as the \(\tilde{O}\left(\frac{k}{\epsilon}\right) \times n\) Subsampled Randomized Hadamard Transform (also called the Fast Johnson Lindenstrauss) matrix. \(SA\) can be computed in \(O(nd \log n)\) time.

- \(S\) as the \(\text{poly}\left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right) \times n\) CountSketch matrix. While the number of rows is larger, \(SA\) can be computed in just \(\nnz{A}\) time.

In this post, we will focus on using the CountSketch matrix for low-rank approximation.

Showing the Existence of a Good Solution in the Row Span of \(SA\)

For our proposed algorithm to actually work, we must first guarantee that some good rank-\(k\) approximation must live in the row span of \(SA\) in the first place. We will use the following thought experiment to show that such a solution indeed exists. We will not actually attempt to recover the solution.

Consider the following hypothetical regression problem:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:hypothetical-regression} \min _{X}\left\|A_{k} X-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}=\left\|A_{k}-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}. \end{equation}\]Note again that this is only hypothetical: we don’t know what \(A_k\) is, because if we did, then we are already done!

Best Solution to Hypothetical Regression Problem

The best solution of \(X\) to Equation \ref{eq:hypothetical-regression} is just the identity matrix \(I_d\), since \(A_k\) is already defined to be the best rank-\(k\) approximation to \(A\), and we cannot increase the rank by multiplying something in hopes of further decreasing the Frobenius norm. This gives us

\[\begin{equation} \min _{X}\left\|A_{k} X-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}=\left\|A_{k}-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}. \end{equation}\]Sketching the Hypothetical Regression Problem with CountSketch

Now take the CountSketch matrix \(S\) to be our affine embedding. We claim that just \(\text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\) rows suffices, instead of the usual \(\text{poly} \left( \frac{d}{\epsilon} \right)\) rows. This is because since \(A_k\) only has rank \(k\), then we could replace it with some other \(n \times k\) rank \(k\) matrix \(U_k\) that has the same column span as \(A_k\). This works because for every \(X\) there is some \(Y\) such that \(A_{k} X=U_{k} Y\) and vice versa. Thus we can replace \(A_{k}\) with \(U_{k}\) without generality, and \(S\) can be taken as a CountSketch matrix for the smaller matrix \(U_{k}\).

Recall our affine embedding result:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:embedding} \left\|S A_{k} X-S A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}=(1 \pm \varepsilon)\left\|A_{k} X-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}. \end{equation}\]To solve for the \(X\) that minimizes the left hand side quantity, recall that the normal equation gives us

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:normal} \argmin_{X}\left\|S A_{k} X-S A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}=\left(S A_{k}\right)^{-} S A. \end{equation}\]Plug in Equation \ref{eq:normal} into the right side of \ref{eq:embedding} to obtain

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:exists} \| A_k (SA_k)^- SA - A \|_F \leq (1 \pm \epsilon) \| A_k - A \|_F. \end{equation}\]What is exciting about Equation \ref{eq:exists} is that it tells us that \(A_k (SA_k)^- SA\) is a \((1 \pm \epsilon)\) approximation for \(A_k\). Furthermore, \(A_k (SA_k)^- SA\) is rank-\(k\) and is in the row span of \(SA\), which precisely answers our original question of whether a good rank-\(k\) approximation in the row span of \(SA\) exists in the affirmative!

To belabor the point, we do not know either \(A_k\) or \(A_k (SA_k)^- SA\); we simply used them to prove that our desired rank-\(k\) approximation in \(SA\) exists.

Considering the Optimal Sketched Solution

Our conclusion from the previous section allows us to conclude that

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:sketch-1} \min _{\text {rank-} k X}\|X S A-A\|_{\mathrm{F}}^2 \leq\left\|A_{k}\left(S A_{k}\right)^{-} S A-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^2 \leq(1+\varepsilon)\left\|A_{k}-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^2. \end{equation}\]However, solving for the left hand side of Equation \ref{eq:sketch-1} is different from normal regression, because the rank of our solution for \(X\) is constrained. Suppose for a moment that we ignore this rank constraint and proceed to solve for \(X\) as per usual using our normal equations. Then by plugging in the normal equations into Equation \ref{eq:sketch-1}, we obtain

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:pyt-1} \|X S A-A\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}= \left\|X S A-A(S A)^{-} S A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} + \left\|A(S A)^{-} S A-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} \end{equation}\]by considering the Pythagorean theorem for the elements row-wise: \(X_i SA\) is a projection of \(X_i\) onto \(SA\) in a rank-\(k\) space, and \(A_i (SA)^- SA\) is the projection of \(A_i\) onto \(SA\).

Equation \ref{eq:pyt-1} tells us that the second term on the right hand side does not depend on \(X\), so we can re-formulate Equation \ref{eq:sketch-1} as

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:smaller-min} \min _{\text {rank-}k\, X}\|X S A-A\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}=\left\|A(S A)^{-} S A-A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}+ \min _{\text {rank}-k\, X}\left\|X S A-A(S A)^{-} S A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}. \end{equation}\]A Simpler Minimization Problem

Equation \ref{eq:smaller-min} reduces our original minimization problem to just solving

\[\begin{equation} \min _{\text {rank}-k\, X}\left\|X S A-A(S A)^{-} S A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}. \end{equation}\]To solve this, let’s begin by writing \(S A=U \Sigma V^{\top}\) in SVD form. We can do this in \(d \cdot \operatorname{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\) time. Then simplify our expression from Equation \ref{eq:smaller-min} to obtain

\[\begin{align} & \min _{\text {rank-}k\, X}\left\|X S A-A(S A)^{-} S A\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} \\ = & \min _{\text {rank}-k\, X}\left\|X U \Sigma V^{\top}-A(S A)^{-} U \Sigma V^{\top}\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} & \text{(substituting SVD representation of $S$)} \\ = & \min _{\text {rank}-k\, X}\left\|\left(X U \Sigma-A(S A)^{-} U \Sigma\right) V^{\top}\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} \\ = & \min _{\text {rank}-k\, X}\left\|X U \Sigma-A(S A)^{-} U \Sigma \right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} & \text{($V^\top$ is orthonormal and does not change norm)} \\ = & \min _{\text {rank-k } Y}\left\|Y - A (SA)^- U \Sigma\right\|_{F}^{2}. & \text{(change of variables from $X$ to $Y$, since $U\Sigma$ has full rank)} \\ \end{align}\]This shows that it suffices to just compute the SVD of \(A (SA)^- U \Sigma\) to solve our original problem!

Issues with Running Time

Unfortunately, we still haven’t achieved the running time we want. Recall that our goal was to find the best rank-\(k\) approximation in time \({O(\nnz{A} +(n+d) \operatorname{poly}(k / \varepsilon))}\). \(A (SA)^- U \Sigma\) is a \(n \times \text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\) matrix, so one might claim that computing its SVD only takes \(O\left( n \cdot \text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right) \right)\), which is within our time bounds. We could also compute \(SA\), its pseudoinverse \((SA)^-\), and the multiplication \((SA)^-U\Sigma\) quickly.

However, the problem is that we cannot multiply on the left by \(A\) within the time bounds, because we have no guarantees about the sparsity of \((SA)^- U \Sigma\). It may as well be a very dense matrix. This means that computing \(A(SA)^- U \Sigma\) takes time at least \(O\left( \nnz{A} \cdot \text{poly}\left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right) \right)\), which does not meet our bounds.

Summary of Current Progress

Now is a good time to stop and review the progress that we have made so far. To recap, our current algorithm works as follows:

- Compute \(SA\). This is in time \((\nnz{(A)})\)

- Project each row of \(A\) onto \(SA\). We just showed that we couldn’t do this in our desired time bound \({O\left(\nnz{A} +(n+d) \operatorname{poly}\left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\right)}\).

- Find the best rank-\(k\) approximation of the projected points inside the rowspace of \(SA\). This is in time \(O\left( n \cdot \text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right) \right)\).

Therefore Step 2 is our bottleneck that we hope to improve. We will do this by approximating the projection of \(A\) onto \(SA\).

Approximating the Projection

Projection is in fact just least-squares regression in disguise. This inspires us to sketch again to reduce the dimensions of the problem.

Recall that previously we wanted to solve for

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:target} \min _{\text {rank-} k \, X}\|X S A-A\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}. \end{equation}\]We can’t sketch on the left anymore since \(X\) appears on the left, so we try to sketch on the right instead. Let \(R\) be an affine embedding matrix, say a transposed CountSketch matrix with \(\text{poly} \cdot \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\) columns. Then we sketch on the right in Equation \ref{eq:target} to change our target to be

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:new-target} \min _{\text {rank-} k \, X} \|X (S A) R-A R\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}. \end{equation}\]It would be wise to first verify that we can compute all our quantities in the desired bounds. Indeed, computing \(AR\) takes \(\nnz{A}\) time, and computing \(SAR\) can be done in \(\nnz{SA} \leq \nnz{A}\) by recalling that \(SA\) cannot increase the number of non-zero entries in \(A\).

Since \(R\) is an affine embedding, by Equation \ref{eq:new-target} we obtain

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:applied} \|X (S A) R-A R\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}. =(1 \pm \varepsilon)\|X (S A)-A\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}. \end{equation}\]We can rewrite our new target in Equation \ref{eq:new-target} to obtain

\[\begin{align} \min _{\text {rank-} k\, X}\|X S A R-A R\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} & =\left\|A R(S A R)^{-} S A R-A R\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}+\min _{\text {rank-}k\, X}\left\|X S A R-A R(S A R)^{-} S A R\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} \end{align}\]by applying the Pythagorean theorem. Then similarly as before, note that only the second term depends on \(X\), so again we have a smaller minimization problem:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:change-var} \min _{\text {rank-k } X}\left\|X S A R-A R(S A R)^{-}(S A R)\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2} = \min _{\text {rank-} k\, Y}\left\|Y-A R(S A R)^{-} S A R\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}, \end{equation}\]where we perform a change of variables to \(Y\). We can do this because the optimal \(Y\) must live in the row space of \(SAR\) and therefore take the form \(XSAR\). Suppose if it did not, then since \(AR(SAR)^-SAR\) is in the row space of \(SAR\), then we could simply remove the orthogonal components to \(SAR\) in \(Y\) to obtain an even better solution, contradicting its optimality.

Analyzing the Runtime

This time round, we have truly solved the problem. Previously, we failed because we could not project \(A\) onto the column space of \(SA\) in the desired time bounds. But this time round, \(SAR\) has dimensions \(\text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right) \times \text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\), and \(AR\) is a \(n \times \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\) matrix that takes \(\nnz{A}\) time to compute, which means that \(AR(SAR)^-(SAR)\) can be computed in time \(n \cdot \text{poly}\left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right) \in {O\left(\nnz{A} +(n+d) \operatorname{poly}\left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\right)}\).

As a result, we can proceed to compute \(Y\) in Equation \ref{eq:change-var} by performing truncated SVD in time \(O\left(n \cdot \text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\right)\).

As noted previously, our solution \(Y\) must look like \(Y = XSAR\) for some \(X\). We can thus solve for \(X = Y(SAR)^-\).

Then by Equation \ref{eq:target}, the final rank-\(k\) approximation that we wish to return is \(XSA = Y(SAR)^-SA\). A final caveat here is that we must return \(Y(SAR)^-SA\) in factored form, because if we multiply out the matrices it is a \(n \times d\) matrix, which does not fit in our desired running time.

Returning the Output in Factored Form

We want to output \(LR = Y(SAR)^-SA\) as \(L, R\) where \(L\) is \(n \times k\) and \(R\) is \(k \times d\).

To do so, recall that \(Y\) is \(n \times \text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right)\) and so we can recover its SVD representation as \(Y = U \Sigma V^\top\). Then let

\[\begin{align} L & = U \Sigma, \\ R & = V^\top (SAR)^-SA, \end{align}\]where \(L\) is \(n \times k\) and \(R\) is \(k \times d\). One can check that we can perform all the matrix multiplications within the time bounds.

Bounding the Failure Probability

The sketch by \(S\) and \(R\) may both fail to be an affine embedding with some constant probability, say \(\delta = \frac{1}{100}\). Then we can simply union bound over \(S\) and \(R\) failing to show that the construction works with small constant failure probability.

Summary

That was a lot of discussion and analysis, but in the end, the low-rank approximation algorithm is very simple.

- Compute \(SA\).

- Compute \(SAR\) and \(AR\).

- Compute \(\argmin_Y \left\|Y-A R(S A R)^{-}(S A R)\right\|_{\mathrm{F}}^{2}\) by truncated SVD.

- Output \(Y(SAR)^{-}SA\) in factored form.

This takes \(O\left(\nnz{A}+(n+d) \text{poly} \left( \frac{k}{\epsilon} \right) \right)\) time overall, which is much faster than applying truncated SVD to \(A\) directly.

References

- Kenneth L. Clarkson and David P. Woodruff. Low rank approximation and regression in input sparsity time. CoRR, abs/1207.6365, 2012. URL: http://arxiv.org/abs/1207.6365, arXiv:1207.6365.

- Tamas Sarlos. Improved approximation algorithms for large matrices via random projections. In 2006 47th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS’06), pages 143–152, 2006. doi:10.1109/FOCS.2006.37.

Related Posts: