Three Important Things

1. Weak-to-Strong Generalization

The problem of weak-to-strong generalization is how a weak teacher model can teach a stronger student to perform better than it.

This is relevant in the context of superalignment, where while we have found traditional success in using RLHF to align models to follow our preferences, such techniques may no longer work when models become smarter than us and we are no longer capable of supervising its outputs.

The weak-to-strong supervision setup in the paper works as follows:

-

Train a weak supervisor by fine-tuning a small pre-trained model on ground-truth labels.

-

Use the weak supervisor to generate a set of labels for a different held-out set of examples. These are the generated weak labels.

-

Fine-tune the strong model with the generated weak labels.

Two main limitations of this setup make it disanalogous to weak-to-strong generalization in the context of creating superhuman AI:

-

Imitation saliency: the strong model may learn to make similar mistakes as the weak model when learning to imitate its behavior. However, the mistakes made by the weak models now will be different from the mistakes made by the models we use to train superhuman models in the future, which probably has salient representations of human behavior

-

Pretraining leakage: many of the tasks that the model is trained and evaluated on are represented in some form in its pretraining distribution. However, superhuman knowledge is likely not implicit in its pretraining data (and may require techniques like self-supervised learning to elicit), which makes the experiment results possibly more optimistic.

2. Techniques for Weak-to-Strong Generalization

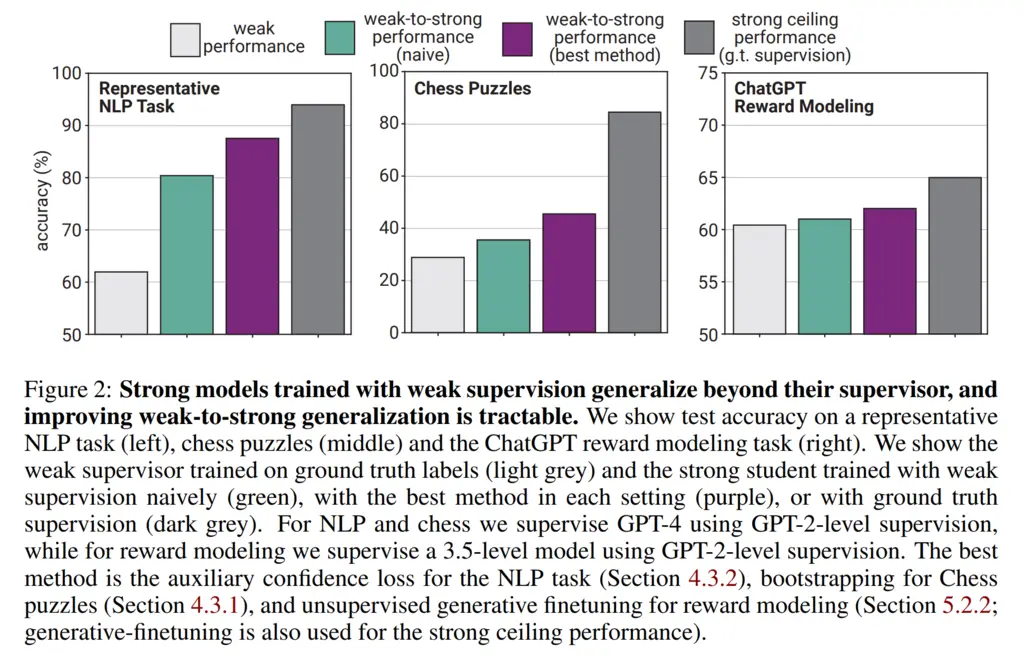

The paper investigates the efficacy of several techniques for weak-to-strong generalization, which they applied on 3 datasets: NLP tasks, chess puzzles, and ChatGPT reward modeling task (proprietary dataset).

The techniques are:

- Naively finetuning on weak labels. This is a baseline approach.

- Bootstrapping with intermediate model sizes. This means that instead of directly aligning a superhuman model, a only slightly superhuman model is first aligned, and then used to align an even stronger superhuman model, and so on.

- Adding an auxiliary confidence loss to the training of the student model. This encourages the strong student model to diverge from the predictions of the weak teacher model when it is confident of its predictions, allowing it to not make the same mistakes as its teacher.

- Generative supervision: the idea is that having more salient representations of the task can help the model better perform the task. In the case of the paper, this was in the context of reward modeling, and they added unlabelled datasets of prompts and any associated responses to the fine-tuning data. In theory, this does not result in any leakage of preference data (which would be ground-truth labels).

Not too unsurprisingly (due to precedence from scaling laws & emergence), naive finetuning allowed the strong student to outperform the weak teacher:

They use the performance gap recovered (PGR) metric to measure how much their methods can close the gap between the strong ceiling (using ground-truth labels), and the performance of the weak teacher.

Of these, it did well for NLP tasks, but still had significant gaps for chess and ChatGPT reward modeling tasks.

3. Fine-tuning on Weak Supervision to Increase Concept Saliency

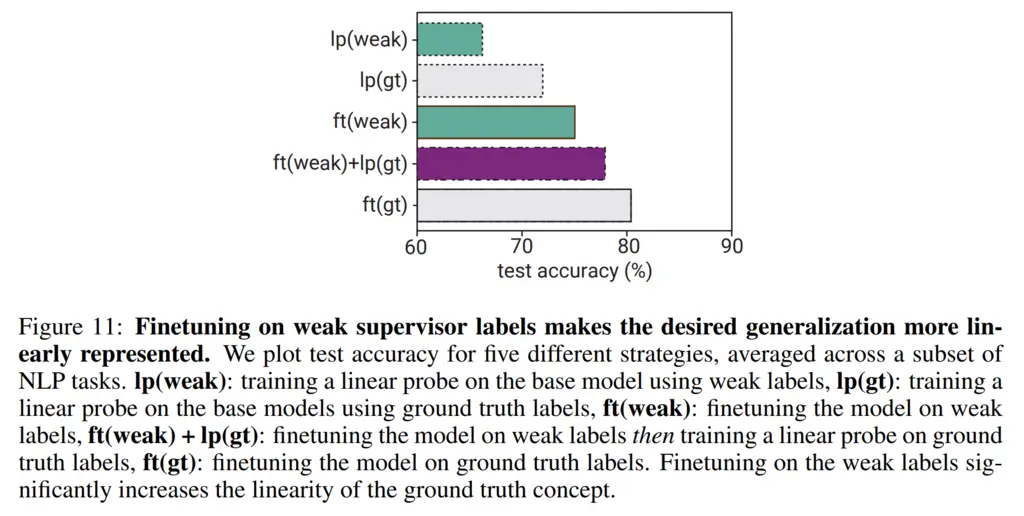

An interesting experiment in the paper is using a linear probe to understand how linearly represented a task is. A linear probe means fine-tuning a single-layer linear layer on top of the model, and hence if it does well it means the concepts can be linearly separated.

They experimented how well linear probes do in the context of NLP tasks.

Going in order of the plots:

- Training a linear probe on weak labels did the worst. Not surprising!

- Doing the same with ground-truth labels was better. Also unsurprising.

- Fine-tuning the entire model using weak labels was stronger. Reasonable since it is more expressive.

- Fine-tuning the model on weak labels, and then training a linear probe on it using ground-truth labels brought it close to fine-tuning with ground-truth labels. This is interesting!

In particular, the last point shows that fine-tuning on weak labels causes the model to acquire more salient representations of the task and makes it more linear, even with respect to ground-truth labels.

Most Glaring Deficiency

A major question I had throughout was what kind of tasks is superhuman performance reasonable, and what weak-to-strong generalization might look like in practice for that. It does not seem well-defined for things like NLP and reward modeling, since what does it mean to be better than humans at something like language, when it is meant for humans in the first place?

Chess is one arena where machines have achieved superhuman performance via self-play, but there does not seem to be much of an alignment problem due to the presence of codified rules. However this precisely causes it to deviate from the ill-posed and complex problems that we face in real life.

Conclusions for Future Work

The techniques for weak-to-strong generalization here could be used in the interim to bootstrap stronger models using weaker models, since labels generated by models are cheaper than having human annotators create them.