Four Important Things

1. OPRO Framework

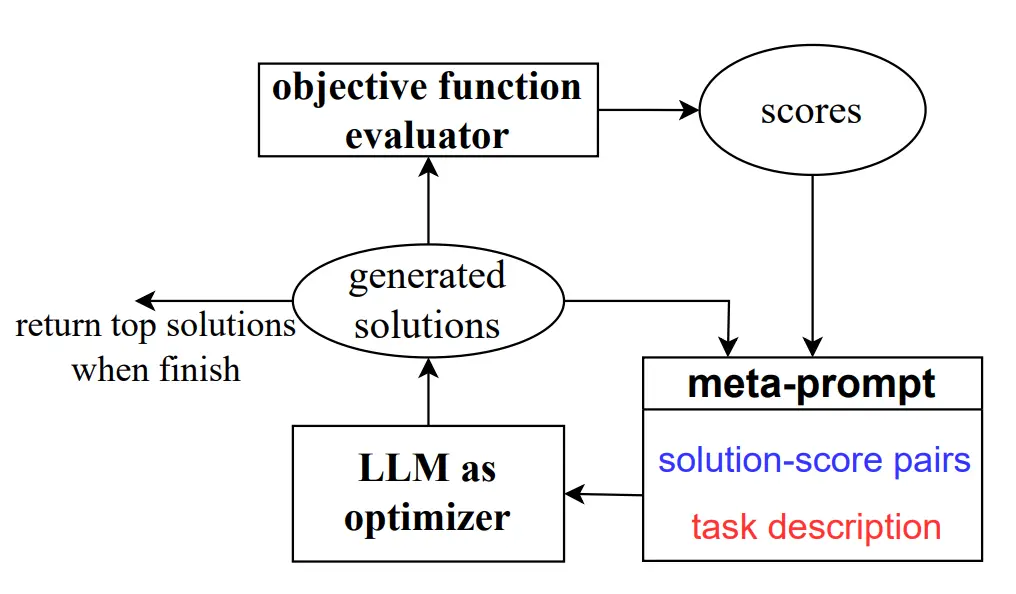

The paper introduces the Optimization by PROmpting (OPRO) framework to make use of LLMs as optimizers.

This works as follows. The user first comes up with a meta-prompt, which defines the problem of optimizing for the prompt that we actually care about.

The example below shows a meta-prompt for optimizing for a CoT-style prompt:

I have some texts along with their corresponding scores. The texts are arranged in ascending order

based on their scores, where higher scores indicate better quality.

text:

Let’s figure it out!

score:

61

text:

Let’s solve the problem.

score:

63

(. . . more instructions and scores . . . )

The following exemplars show how to apply your text: you replace <INS> in each input with your

text, then read the input and give an output. We say your output is wrong if your output is different

from the given output, and we say your output is correct if they are the same.

input:

Q: Alannah, Beatrix, and Queen are preparing for the new school year and have been given books

by their parents. Alannah has 20 more books than Beatrix. Queen has 1/5 times more books than

Alannah. If Beatrix has 30 books, how many books do the three have together?

A: <INS>

output:

140

(. . . more exemplars . . . )

Write your new text that is different from the old ones and has a score as high as possible. Write the

text in square brackets.

Once the LLM produces a new solution, it can then be evaluated, and the solution-score pairs added back into the meta-prompt, allowing the next iteration to learn from previous trajectories.

This loop of optimization continues until the LLM plateaus in the scores of the proposed solutions, or the number of optimization steps is reached.

Overall, the OPRO optimization loop looks like this:

In practice, they sort the past solution-score pairs in ascending order in the meta-prompt so it can perform in-context learning to improve future trajectories. This is probably due to the well-known recency bias in ICL, where it has a higher probability of outputting things similar to the last few demonstrations.

2. Optimization Challenges

There can be optimization instability and high variance at the start when solutions are generally low-quality. They mitigated this by generating multiple solutions per step, which increases the probability of getting at least one decent solution.

They also noted how temperature can be used to manage the exploration-exploitation trade-off: using low temperatures for exploitation, and higher temperatures for exploration.

3. Applications to Classical Optimization

They applied OPRO to the classical optimization problems of regression and traveling salesman problem (TSP).

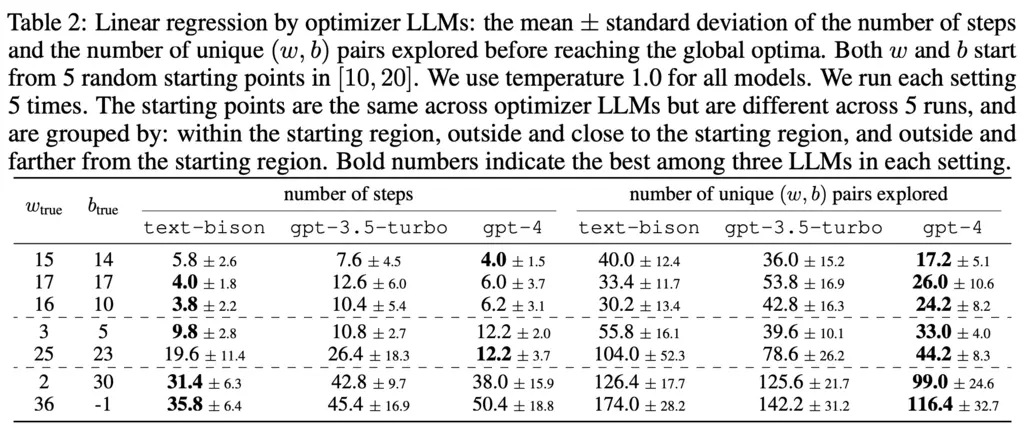

For regression, the difficulty is varied by controlling how far the initial proposed weight and bias coefficients are from the true values, and we note the unsurprising trend that starting from a poorer initialization resulted in more steps for convergence.

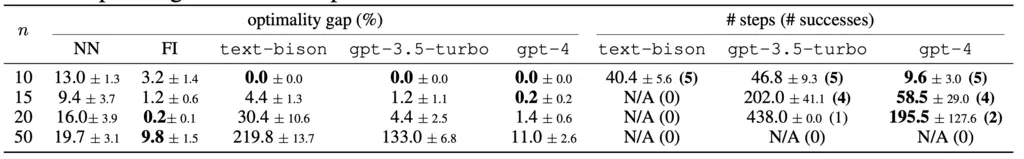

In TSP, the difficulty is varied by increasing the number of stops \(n\), and the LLM fails to find the optimal solution for \(n > 10\).

4. Prompt Optimization

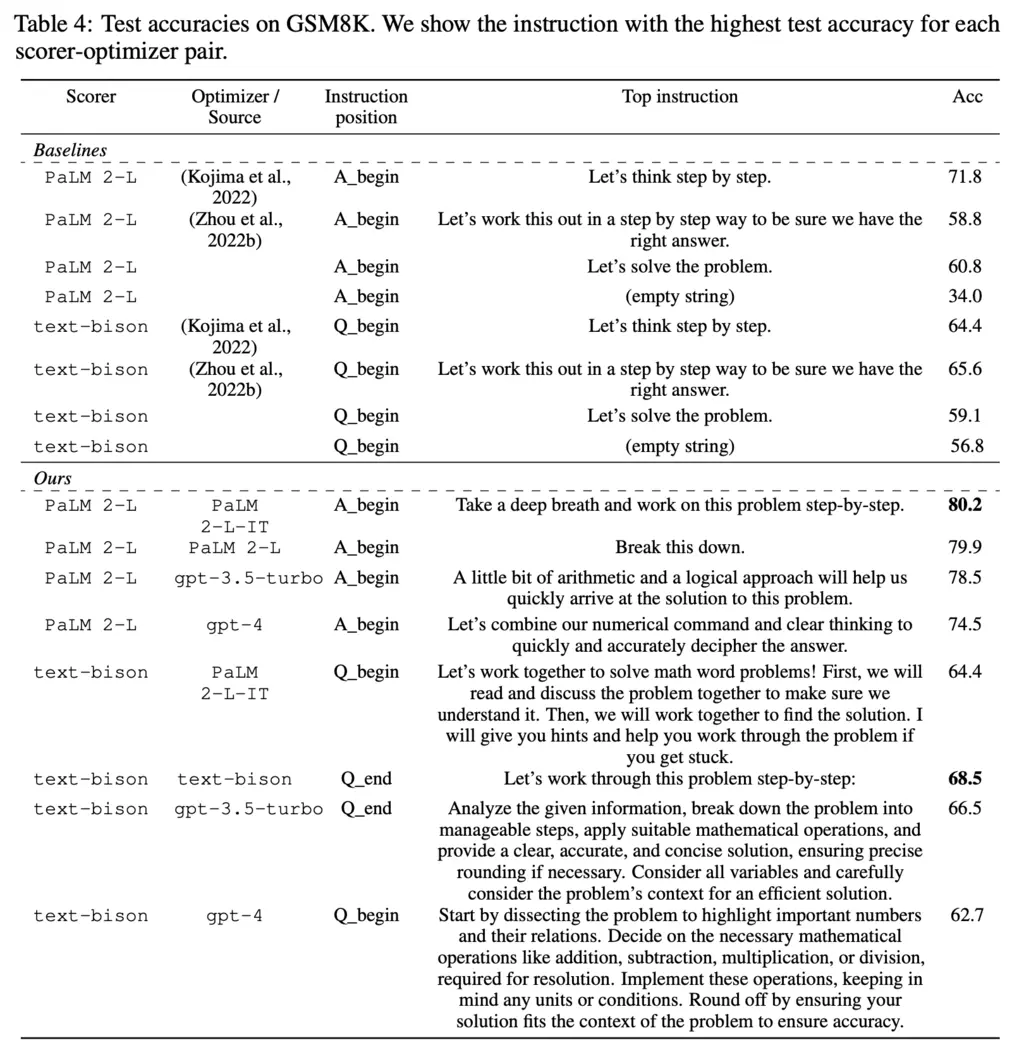

The authors ran OPRO to optimize for prompts on GSM8K, and found that the top performing ones were different but semantically similar to the popular “Let’s think step-by-step” 0-shot CoT prompt:

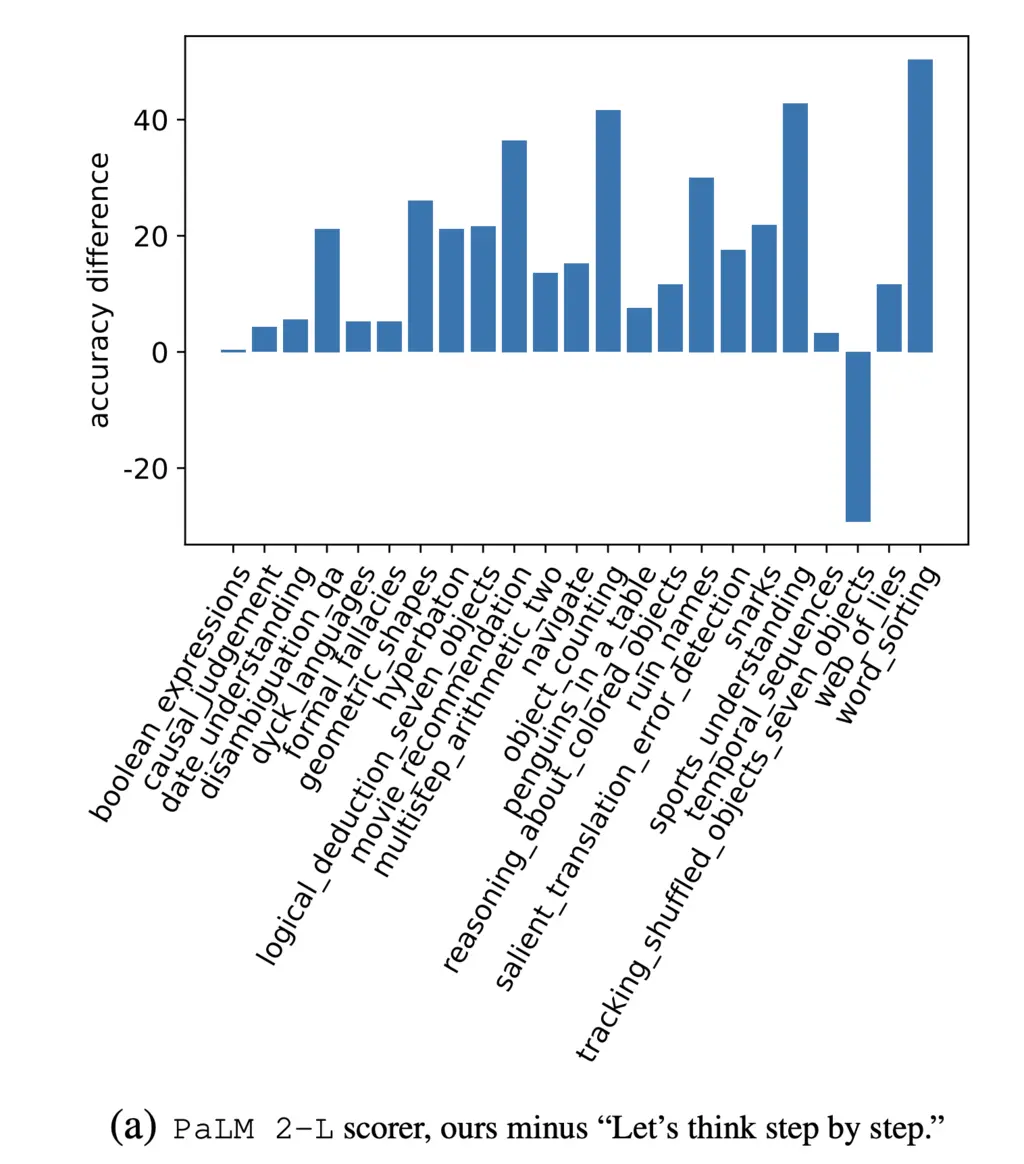

They also found that their optimized prompts outperforms “Let’s think step-by-step” on the Big Bench Hard (BBH) dataset:

Most Glaring Deficiency

The paper addressed many questions I had about its design choices in its ablation section, such as ordering of the previous solution-score pairs and comparisons with evolutionary techniques.

One idea I had that was not addressed was the use of an “exploration-exploitation scheduler” to anneal down the temperature as better candidate solutions were found. Instead, a fixed temperature of 1.0 was used for their experiments. This is similar to how \(\epsilon\) is decreased over time in \(\epsilon\)-greedy RL algorithms to encourage initial exploration, and then eventually preferring exploitation.

Conclusions for Future Work

This paper provides a simple and practical method of optimizing prompts for LLM practitioners. I believe the general framework will be very impactful for years to come due to the universality of the approach.